Project «Voices of Jewish settlements. Minsk region.»פיתוח קשרי התרבות בין העמים של ישראל ובלרוס

|

|---|

Website search |

|

MainNew publicationsContactsSite mapVitebsk regionMogilev regionMinsk region |

Traveling with Arkady ShulmanFOLLOWING THE PASTSunny days in early May. It's hot during the day though a spring cold can still be felt at night. It hasn't rained for several days. And the passing cars raise clouds of dust on the road. For a whole week our minibus will be driving in northwestern Belorussia. We visit cities and villages that used to be predominantly populated by Jews. We are trying to chase after time that's already gone. It's impossible to do – what's gone is gone forever. The expedition is organized by the Museum of the History of Polish Jews. We've got an interesting and competent company here. Andrzej Tshetsinsky, professor of the Lyublin University specializing in Jewish culture; Krzysztof Belyavsky, the museum's employee who is also in charge of well-functioning of the website “Virtual Shtetle“; a hystorian from Minsk Alya Sidarovich; polish documentalists, employees of Grodno museums, postgraduate and undergraduate students of the Grodno University, and I, a journalist who joined them. We are one and a half Jews for ten persons. Half of Krzysztof and I. It might have been strange some time ago for a non-Jew to study Jewish history. And not without success, I should say. But how on earth could we possibly find a Jew in Poland or Belorussia if almost all of them had left the country? I think it's not the scientists' origin that matters but the objectivity of the results achieved. And I wrote about “one and a half Jew“ neither because I read the Isaac Babel's story about “one and a half Hebe“ nor for some other solid reason, but just because there were a couple of jokes about it in the bus. Those were not mean or prejudiced jokes – just jokes for the sake of a joke. I joined the expedition in Rakov; they had already visited the Grodno Oblast before. In Rakov they finally stayed for a night, and there I was the following morning. It was not difficult to get there. It's only in a 40 km distance from Minsk on the route for Vilnius. I was waiting at the bus stop near the gallery-museum of Yanushkevich brothers.  Rakov. Yanushkevich gallery.

Rakov. Yanushkevich gallery.

We were met by Felix Yanushkevich, a well-known Belorussian artist and restorer. I saw his works in museums and picture galleries. In the 1980s these were canvases painted in the Socialist Realism style but with years his art transformed. Apart from creative spirit he possesses an entrepreneurial one and, combined together (aren't all entrepreneurs artists in a way?) these two qualities brought interesting results. Yanushkevich opened a gallery-museum in Rakov. Before the World War II there was a Jewish house in this very place at 1, Vilenskaya Street. A baker Yosel Krasnoselsky, whose family died in the Rakov ghetto, lived in this house. Before the ghetto was demolished the Krasnoselskys had hidden all their belongings in barrels and buried them near the house. They hoped to come home later and dig out their things. But Yosel and his family died in the ghetto. After the war those hidden barrels were found during construction works in the house yard. The belongings of the vanished family were carefully preserved, not a single thing was thrown away. When Felix became the owner of the house he faced it with brick and made an interesting exterior design. For example, the gallery-museum’s name on concrete panels is written in Belorussian and transcribed in Latin letters. The museum occupies all the floors and the yard of the house. The books in Yiddish left by Yosel Krasnoselsky are exhibited there, including Maxim Gorky’s novels. There’s also a lot of household items: kitchen utensils, bottles, a kerosene lamp, drug pots, various boxes, a chest of drawers – I think all those things are international. Polish books are preserved as well.  Pages of Jewish books.

Pages of Jewish books.

Jewish books preserved by Yanushkevich.

Jewish books preserved by Yanushkevich.

In the basement there are several helmets. During the war they were protecting the heads of German soldiers. On the second floor there is Felix’s workroom - with paintings on the wall, a canvas on the stretcher, tubes of paint, an easel, a sketch-book, and brushes. The guests of the gallery are curious to see an artist at work while he’s telling about what he’s painting. A good talk can even lead to some visitor’s buying a painting. Felix is a great story-teller. If necessary, he can speak Belorussian, Polish or Russian. On the third floor, looking through the window at the street, Felix told us about the former inhabitants of Rakov, mentioning that the family of an honored Belarusian artist Mai Danzig’s mother lived nearby. It’s a pleasure listening to Felix. The tour of the Yanushkevich’s gallery starts and finishes on the first floor. …A long table – the same ones used to be placed in taverns. The benches also resemble those of a tavern. Old but solid furniture. Our expedition had both breakfasts and dinners there. The food is simple and plain but delicious. Felix says that his wife cooks it. A shtof-bottle of samogon “on the house” appears on the table, just like in good old times. It’s a beautiful old bottle, “just a little, to keep the company” as the saying goes. I tried it and it was good. Jam and pies were served for dessert. The kids of Felix are also here playing piano and clarinet. Not Van Cliburn yet but they have a lot of time ahead. Interesting conversations in a good company – we all had a great time. A wonderful combination of a Jewish tavern and a szlachta house. Naturally it costs some money. But who said we should not pay for pleasures? You may believe me that I’m not telling about this place because the Yanushkevich gallery-museum paid me for an advertisement.  Rakov. The street of synagogues and yeshiva.

Rakov. The street of synagogues and yeshiva.

Then we had a brief tour of the town. We have specific interests, so Felix accompanies us to a Jewish cemetery where the history of Rakov is engraved on the tombstones. So many different people are buried here: Torah connoisseurs and commons, watermen and balagulas, righteous men and yentzers, local philosophers and those who were considered lunatics (sometimes they were one and the same person). A stone staircase leads to the cemetery gates and to a pine tree hill behind them. Jewish cemeteries are usually located on a hill, the oldest tombs being placed on the top.  Rakov. The gates of the Jewish cemetery.

Rakov. The gates of the Jewish cemetery.

The cemetery gates are padlocked. “Who would come here?,” says Felix. “There are no Jews left in Rakov, and those who come to visit the graves of their relatives take the key that is kept by trustworthy people.” Keeping the cemetery locked is a necessary measure: the old tombstones used to be taken for making house bases or for road construction works. People made out excuses saying that no one will ever visit these graves. Who would, indeed, if almost all of Rakov’s Jewish population was executed by fascists during the war. And those who miraculously managed to escape went to other cities, and more often to other countries. About twenty years ago I met an old man who used to live in Rakov before the war. He came from Israel where he had come to live in early 1990s with his children and grandchildren. The old man cried telling about his hometown. He said that he often sees it in his dreams and that he’d never seen a more beautiful place in his whole life. He was a partisan during the war, and when it was over he returned to his hometown. “Then why did you leave? ” I asked him. “You cannot live on memories”, he said in a shaking voice. “Every day I would come to the place where my family was executed, and I cried. If I continued like this, I would go crazy.” I don’t know if that old man is still alive but our conversation came to my mind when we reached the gates of the Jewish cemetery. Felix told us that in the 80s, when there was still no fence here local people would pass through the cemetery walking on the graves on their way to the marketplace and back, to take a shortcut. And on the place where now stands the monument to the Jews of Rakov murdered by the fascists during the war kids used to play football. “I told the kids, ‘Don’t play football, have respect for the dead resting here’, and they replied, ‘OK, they’ll be our fans.” A sad, black humor. The fence around the cemetery was built in the beginning of the 1990s, when the “iron curtain” put by the Soviets fell and former residents now living in Israel, the USA, and other countries started to come. It’s written on the plaque at the gates that the cemetery was fixed up by the descendants of Barney and Lea Gurvitz families living in the South African Republic and by Aaron Gringolts from Israel. We read the words on one of the cemetery’s matzevas: “Here lies our dear mother, who left us so suddenly. Shoshana-Elka Gringolts, Abraham’s daughter. Deceased on Shevat 16, …”; unfortunately we couldn’t make out the year of her death. The locals of the same name were usually relatives. I think Aaron Gringolts who took part in the cemetery’s restoration belongs to Shoshana-Elka’s family.

At the Jewish cemetery.

At the Jewish cemetery.

We saw the year 1921 written in letters as 5681, according to the Jewish calendar, on one of the old tombstones that was used to build the fence. In all likelihood this tombstone was part of the old pre-war fence. Most part of it was stolen and this one stayed to remind us that back in 1921, unquiet and shaken by war, the Jewish community of Rakov built this fence around the cemetery. We were told that there should be a passage in the fence somewhere but after searching for 5 minutes we decided to get over the fence, luckily all members of our expedition looked rather sporty. The matzevas at the Rakov’s cemetery are placed in two large groups. Pines and grass grow between them. Probably this is how the burials were structured but more likely the matzevas were stolen from here. And the trees stayed the silent and only witnesses of those times when the Rakov's cemetery was still functioning and the old Jews were coming here to take care of their future grave site. On the spot between two groups of matzevas there is a monument to 112 Jews murdered by the Nazis and their allies. It was only after returning from the expedition that I read in the Internet that the Jewish cemetery in Rakov is one of the oldest in Belorussia. It was founded back in 1664. Only around 700 tombstones have been preserved. The oldest surviving grave is dated 1767. The most recent graves date back to the 1960s. We did not find the oldest matzeva, we could only find the ones as old as the end of the 18th century, and professor Andrzej Tshetsinsky read what was written on them. In 1960s this cemetery was used as a burial place for the Jews living their final days in Rakov and for those brought from Minsk, whose parents had been buried here and who requested in their will to be buried beside them. Rakov is an old settlement that was given the status of a shtetl in 1579. A Dominican catholic convent appeared here in 1686, and a Uniate Basilian one was built in 1702. Most probably the Jews started to settle here in the times of the Rzeczpospolita, in the first quarter of the 17th century. They were farmers of taxes, drinking and salt fees, land tenants, and craftsmen. Pottery and tiles from Rakov were well known far beyond the place. 2.168 Jews lived here in 1897 making up 59,5% of the settlement's population. This place was also widely known for its two famous horse fairs. A big market was held on Mondays. The “privilegies” for holding fairs and trading were granted to the shtetl by the King August III (in the middle of the 18th century), these “patents” were used until the war. “In the town of Rakov there's a well-developed manufacture of winnow mills, wooden threshers and hay cutters sold in the northwestern guberniyas as well as in Courland and Estland. The pottery and tile production was wide-spread in the towns of Zembin, Ivetets, Rakov, whose traders sold their earthenware and green tiles locally.“1 In the interwar period Rakov belonged to Poland. It was a time of the town's “golden age“. After the Riga peace treaty of 1921 a new life started for Rakov which became a border Poland town and the smugglers' “capital“. There lived a pani Fedorovicheva in Rakov. She was addressed as “most illustrious pani“, having deserved this honorary title thanks to her fumatory. Her hams and smoked meat products were sold to Berlin, Dresden, Warsaw. The famous Krakow ham originated from Rakov up to 1939! In the '20s-'30s of the 20th century Rakov roared with foxtrots. The orchestras played at nearly every restaurant. And there were around a hundred of them, always full of clients. The town's 134 shops never suffered from the lack of customers as well. There were even brothels in Rakov. The gold was transferred back and forth through the border, and part of it remained in the town. People say that buried treasures were found here even after the war. Local craftsmen produced ceramics widely known in the region. On the old pictures you can see a two-storeyed red brick trading house in place of the present-day local council building. The old residents remember how difficult it was to take it to pieces during the post-war subbotniks. You can't help but be surprised looking at those old pictures that somehow introduce you to the images of a different world – big houses, beautiful balconies. Stores, shops and restaurants in the central street. Some of them were destroyed by time, other ones – by the “builders of the new life“. But it's during the war that Rakov's architecture suffered the most losses. It was burnt almost completely. Ilya Ehrenburg, who visited this place in the first days after his release, wrote about it. Starting from September, 1939 Rakov was part of the Soviet Republic of Belorussia. A year before, in 1938, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of BSSR gave up the term “shtetl“ and the settlements were since ordinarily called “urban-type settlement“. The word “shtetl“ had a warm feeling in it while the “urban-type settlement“ felt so indifferently. And what is more, Rakov was reduced to a village. Later, though, he became an urban-type settlement as it was before. There were four synagogues in Rakov before 1941. Now there are none. One of the former synagogue buildings remained though at 32, Pionerskaya Street. It used to house the yeshiva and the synagogue. After the war there was an integrated industrial complex here, and now there's a company producing doors and windows. The house is rebuilt, it's covered with siding and all of its windows are plastic now. When we walked to this building the neighbors came asking us “What are you doing here?“ We answered that we just wanted to take pictures of the former synagogue building. They exchanged surprised looks and asked us in disbelief: “Was it really a synagogue?“ Only one of the old people who was born right after the war said: “Yes, I guess it was“. Not only synagogues but also other religious buildings and structures vanished. In the '50s and '60s six churches were demolished in the Rakov parish. It's then that the wonderworking icon of the Holy Mother disappeared. The local vandals burnt down the wooden chapel in the end of the 1980s. Latterly the parishioners built a new, stone chapel on the sacred well. The Orthodox and Catholic churches are being restored or rebuilt now. Not synagogues, for there are no one left in Rakov to build or restore them for. The old people who were born here before the war can still understand Yiddish, though they almost forgot the language; they even know Jewish songs. Rufina Bolotnik (nee Rusetskaya-Matskevich) attempted to sing something in Yiddish. More than 70 years have passed. The memories of most events have faded. 928 Jews resided in Rakov before the war. The most horrific period began in the summer of 1941, when Rakov was occupied by the German-fascist army. On the very first day of the occupation the Wehrmacht police was formed and the robberies of the Jewish property began. Among those polizei who “distinguished“ the most during the robberies were Anton Shidlovsky, Yan Tsibulsky, Vladislav Kuryan, Yan Lukashevich, Yan Aleshko, Vasily Yatskevich.2 The first execusions of the Jews are mentioned in the reports of the head of police security and SD, sent to Germany from the USSR. The report #36 dated 28 July 1941 read as follows: “...the actions were performed in Rakov, located in about 40 km from Minsk, as well as in the forests to the north of the Minsk-Borisov-Krupki line. During these actions were liquidated 58 Jews, functionary communists, agents, criminals and soldiers out of uniform who were suspected in connections with groups of partisans. Besides, 12 Jewish women were shot down for being communists' propagandists during the war with Poland.“ 3 In August of 1941 the Jews of Rakov were concentrated in the ghetto. Horrific facts are mentioned in the book by Marat Botvinnik “Monuments of the Genocide of the Jews of Belorussia“, with reference to the archive documents. “Bloody executions of Jews in Rakov who had been living for ages in this quite place, were held from August 1941 till February 1942. During this period the Hitlerites and gendarmes drove all the Jews to the ghetto concentration camp, guarded thoroughly by local polizei and gendarms. On August 14, 1941 the Hitlerites held the first execution of Jews. They took 45 persons, gave them spades, as if for works, and drove them to the forest in 2 km from the shtetl. There they made them dig holes and once the work was done, the Jews were ordered to lie in those holes face down, and the fascists shot all of them by machine guns.“ 4 The same scenario written by Berlin was used in many ghettos. At first they took the strong and respected men who were able to inspire people to revoke and lead them to the forest. Those men were killed the first. At various pretexts they were taken from the shtetl, usually at the pretext of construction or road works, and none of them ever returned. “In a week, on August 21, 1941 the Hitlerites detained the Jews walking to the shtetl on the Minsk-Rakov road. 14 persons were shot down at once, and others were driven to the Rakov ghetto.“ 5 In the first month of the occupation some Jews hoped that they would be able to live peacefully in shtetls and villages till the war is over, and that the fascists would not touch the civilians. So those who had relatives in the country went to stay with them, coming from one hell to another one. In September 1941 a native of a farm at the Alekhnovichi station, Yasinsky, was appointed to the post of the police commander, and a man by the man of Survillo was made his assistant. They constantly demanded the Jews to give them their clothes and shoes, which were later presented to their lovers. After freeing Roslovskaya, the lover of Hendel, deputy Gebietcomissioner of Vileyka, a lot of furniture, kitchenware and personal belongings taken forcefully from the Jews were found in her barn. On September 26, 1941 that very Hendel made the Jews to bring the Torah scrolls from the synagogue to the town square and ordered to burn them, while the Jewish girls were made dancing and singing “Hatikwa“. “On September 29, 1941 (the Jewish New Year's Eve) the Hitlerites gathered a big group of Jews from the ghetto (men aged from 16 to 50), put them into cars and drove them to a forest in 2 km from Rakov. There they were made to dig holes. When that was done, the gendarmes counted 105 (112) men, made them lie in the holes face down and shot them by the order of P. Dobel. Then the drunk chasteners decided to have some fun. Those of the Jews who were left alive were taken back to the Rakov ghetto and forced to sing and dance. After the “concert“ all the Jews were ordered to lie face down and the chasteners began to shoot them at random. When the Hitler's cutthroats thought that the barber did not sing well enough they just chopped off his head with an axe.“6 We went to the site of execution of those 105 (112) Jews by bus, taking the same route as those people doomed to die more than 70 years ago. We were going on the road for Radashkevichi to the village of Buzuny. Stanislav Romanovich Supranovich was waiting for us there. He was 10 years old back in 1941.  Rakov. Witness to the execution of Jews

Rakov. Witness to the execution of JewsStanislav Romanovich Supranovich . He accompanied us to an old oak tree in the forest. - Here's the place where the Jews were executed, - says Stanislav Romanovich. There is no monument or a memorial stone. The old tree itself is a sort of scary monument. As if the nature decided to mark this place. The lower branches intertwined and bent almost to the ground. There's a big moss-covered hollow in the trunk of the tree. The gnarly bark is blackened either by time or for some other reasons. - Three boys were herding cows and they saw the Jews being driven to the site of execution, - Stanislav Romanovich continues after a pause. - When they heard the shots they got scared and ran away. Coming back in a couple of hours they saw the sand... They were already buried... There are fresh holes and pits dug near the oak tree. “The black diggers“ were looking for the “Jewish gold“. They don't fear neither God nor people. - Two of the Jews managed to escape execution. - remembers Stanislav Romanovich Supranovich. - They lived at our farm, and later hid away in the balka forest. An old man and a woman... They left in about two months. What were their names? I wish I could remember. I never saw them since. I don't know if they survived the war. I knew Hayim, who survived the executions in Rakov. He lived in the shtetl after the war.  Rakov. Monument to the murdered Jews

Rakov. Monument to the murdered Jewsat the Jewish cemetery. The remains of the executed Jews were later reinterred at the Jewish cemetery. In July 2005 a monument was erected here with the financial aid of the Lazarus Fund. There's a text in Belorussian, Yiddish and English engraved on the granite stone: “To the victims of Nazism. 112 Jews of Rakov village were massacred here in the fall of 1941“. A horrific tragedy took place on February 4, 1942. “The police commander Nikolai Zenkevich ordered to all the remaining Jews to get ready for being transported to Minsk. When people gathered at the Kholodnaya synagogue they were ordered to put all their valuables aside and enter the synagogue. No one was let out, and those who tried to escape were killed by the Hitlerites. The doors and windows were shut tightly, the walls were poured with gasoline and set on fire. The kids who attempted to escape were taken at the point of the bayonets and thrown back on people's heads. Local polizie took most active part in this heinous massacre. In those moans and cries for help died the Jewish population of Rakov, 920 (950) persons in total, most of them women, kids and old men“.7 Even nowadays the old residents of Rakov remember this story told by their parents, saying that the smell of burnt human flesh stayed in the air for a month after the tragedy. The Romanovskys family lived near the synagogue where the Jews were burnt. Yadviga Romanovskaya still remembers that gruesome day. - My father and I saw it. When they locked the Jews in the synagogue, my father saw the rabbi who was walking toward the synagogue. My father said: “Where are you going? Your people are being killed there“. And the rabbi replied: “The shepherd should be where his sheep are“ and went into the fire. The Lithuanian police were real monsters... Yadviga did not continue her story, she cried and went back into her house. The document confirming this tragedy is kept in the National Archives of the Belarus Republic. “On 4.2.1942 a ghetto with 100 prisoners was liquidated in Rakov. The Jews from the ghetto began to incite the local population...“8 Why only 100 shot ghetto prisoners are mentioned? How did the Jews incite the population? Did they just refuse to praise the occupants who were killing them? Or were they just saying that the fascists would be done sooner or later and that they would pay for the people's suffering? The document kept at the Federal Archives of Koblenz (Germany) also testifies to the execution of 4 February 1942. “On the 4th of February a small group of security police and SD, under the orders of Security Police and SD, was sent to the shtetl of Rakov... It had the assignment to execute the Russian Jews who lived there. All the Jews – men, women, children – were kept under guard in one of the houses. They were taken from there to a nearby valley. Then they were divided into groups and shot in the back of the head. 100 persons were killed in total. The execution is mentioned in the report #168 of February 13, 1942.“9  Rakov. The road to the site of Jews' burning.

Rakov. The road to the site of Jews' burning.

Did the fascists and their allies from the local polizei shot down the Jews in the nearby valley and burn them in the synagogue on the same day? Or maybe part of the Jews escaped from the synagogue and were shot in the vicinity of Rakov? Ilya Ehrenburg visited Rakov on the next day after being freed, on July 4, 1944. “In Rakov, - he wrote in his book 'People, years, life' – I went to the senior priest of the local church, Ganusevich. He was sitting there, old, quiet, among the prayer books and faded photographs. He saw the Hitlerites set the house on fire. A desperate woman threw her child out the window; a “torch-bearer“ ran up, took the child indifferently, as if it were a char, and threw him back into the fire. The priest was shaking his head: “I could not imagine that such heartless people exist on earth... They took an old priest from Kleban who was ill and could not walk, and tortured him to death...In Loras they gathered everyone at an Orthodox church and burnt it down... In Pershai they killed two priests. It's written in the Book: 'He reveals mysteries from the darkness and brings the deep darkness into light; he increases the nations, and destroys them: he enlarges the nations and guides them; He deprives the World's leaders of reason, and sends them wandering through a trackless waste.' I'm an old man, but how the young ones will live after this?..“ “The senior priest of the church Ganusevich, with whom I was talking to at length, told me about the massacre of Jews. He told about it in details. He had a toothache and was at a Jewish dentist's during the negotiations. The dentist thought that they would kill him. The Germans insisted that he should be kept alive until he filled out a tooth. The fascists, having fun, asked the locals how long it would take. If half an hour it's OK, if two hours, it's too much as they were in a hurry.“ In spite of his age, the priest Ganusevich helped the doomed people and saved Jewish children. “A nun Yekaterina, who was called Sister Katarzyna, gathered Jewish, Polish and Belarusian children together in Rakov. There was a lack of food at the orphanage, and Ganusevich, who was a friend of Katarzyna's, drove around the villages and begged people to take the orphan kids. They were converted into Catholic religion and it gave them a chance for staying alive.“10 Was Dora Sheivehman one of those saved kids? In the first days after his liberation Ilya Ehrenburg talked to her, together with a Soviet Army major. The girl was afraid to give her real name, surname and nationality. She insisted that she was Dasha Nesterenko, a Belarusian. I met people who felt the fear experienced in childhood for their whole lives. As a matter of fact, the Soviet power regularly reminded them of that fear – by the “doctors case“, “passportless loafers“, by antisemitic articles in the newspapers and difficulties with finding a job, and etc. These people did not want to remember the surnames of their parents and their nationality. And sometimes such memories were stronger than fear. Of course, the Jews took attempts to escape. We know about some of them. Genya Milshtein was found in the field after the massacre in Rakov, brought to the ghetto and thrown in the burning house.11 One of such episodes is described in the book by Leonid Smilovitsky “The catastrophe of the Jews of Belarus. 1941-1944“ (Tel-Aviv, 2000) In February 1942 Abram Mazelev and Aizik Kagan were working in the forest when they learned about the massacre in Rakov. They fled to Kuchkuny where they were helped by a forester Konstantin Romanyuk who gave them food and warmed them but did not dare to let them stay. Abram and Aizik went to Gorodok and then to Radoshkovichi, where the chasteners were taking their action. Mazelev hid at an attic, and Kagan got caught and was promised life if he gave away all of his possessions. When the Hitlerites took all his valuables they shot him down. When they were coming up to the attic for Mazelev, he jumped down to the ground and feigned death. At darkness he fled to the forest where he hid until the spring of 1942. In the forest he met Abram Milshtein from Rakov and Hayim Persky from Volozhin. Hungry, they came to the village of Stary Rakov and asked for some food. The son of a peasant, whose door they knocked on, killed Mazelev, and Milshtein and Persky managed to escape. A peasant Milyashkevich agreed to hide Persky in a hiding place under the stove in his house. But Persky could not stand his sufferings, “fell into melancholy“ and died in the hiding-place. Only Milshtein out of three of them survived: he found partisans and begged them to take him to their detachment, where he was fighting until the liberation of the Republic in July 1944.“12 Abram Davidovich Milshtein, born in 1908; fought in the partisan brigade named after Suvorov, in the territory of Baranovichi Oblast.13 Brothers Daniel and Wolf Kaplan were hiding in February at a peasant they knew, but they were arrested following a denunciation. The day before the execution they escaped to the shtetl of Gorodok, getting frostbites on their feet, but they were not accepted there. Kaplans hid in the concentration camp of the Krasnoye shtetl, and then escaped to join the partisans. They were fighting in the detachment named after Stalin and demonstrated bravery. Their countryman Naum Moiseyevich Gringolts after the massacre in Rakov went from Gorodok to Lyuban passing through Vileyka, met the partisans and fought in the brigade named after Dovator of the detachment named after Sverdlov; and Tevel Gorbuz was among the partisans of Tchkalov brigade, the same brigade of the detachment #4 “For the Soviet Belarus“ where David Kaplan fought. Alexander Semyonovich Gurvich fought in the partisan brigade named after Chapayev and died in the battle with the fascists in 1943. He was 46 year old. Sofia Zhilinskaya was only 20. She fought in the partisan brigade “Shturmovaya“. Mikhail Shnit, fighting in the brigade “For the Soviet Belarus“ was of the same age. Masha Isaakovna Gurvich, born in 1903, and Nehama Alexandrovna Gurvich fought in the 106th partisan brigade and died fighting. 179 Jewish families of the Rakov shtetl died in total.14 13 of those families had the name Botvinnik.15 1050 Jews died in Rakov in the years of the Holocaust.16  Rakov. The monument on the place of the synagogue where the Jews were burnt alive.

Rakov. The monument on the place of the synagogue where the Jews were burnt alive.

In 1965 a monument was erected on the place of the Rakov synagogue with the words on it telling about this tragic day and innocent victims in Russian and Yiddish. The monument was made to resemble a Jewish tombstone. A tree with cut off brunches. Such monuments were traditionally placed at cemeteries, on the grave of the last member of a family – it meant that with his death the family went extinct. Professor Andrzej Tshetsinsky said that he had encountered similar monuments at Catholic cemeteries...  Uri Finkel.

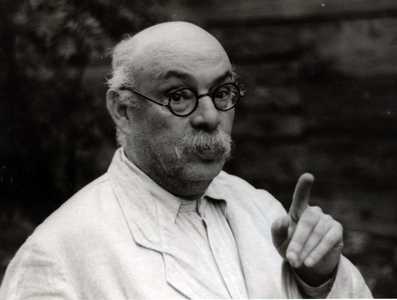

Uri Finkel.

Hirsh Finkel. 1870.

Hirsh Finkel. 1870.

Uri Finkel, a Jewish writer, theorist of literature and publicist, was born in Rakov and lived here before and after the war (1896, the Rakov shtetl, Minsk guberniya, - 1957, Minsk). He wrote in Yiddish, the language of his parents, the language of his childhood and youth. Uri was born in a big religious family and had a traditional education. His father Hirsch-Shlomo, the butcher, hoped that his firstborn would become a rabbi and Uri himself dreamt about it as a child. But life had different plans on him. Starting from 1921 Uri Finkel worked at the publishing department of the Ministry of Education of BSSR. He was the editor of the first Jewish paper “Rusta“ of the Red Army and he edited the “Di commune“ paper as well. He worked at the Jewish sector of the Academy of Sciences of Belarus, and later in Belarusian Jewish papers “Veker“ and “Oktyaber“. He became widely known for his books of the Jewish literature classics Mendele Mocher Sforim and Shalom Aleichem. In 1930-1938 he taught at Minsk Pedagogical Institute. His parents continued to live in Rakov, on the territory of the “bourgeois“ Poland, and for many years he did not have the possibility even to write to them. Only starting from September 1939, after Western Poland had been annexed to Belorussia, Uri Finkel who was father of 5 children and a famous writer at the time could visit his parents, brothers and sisters.  Lisa Finkel.

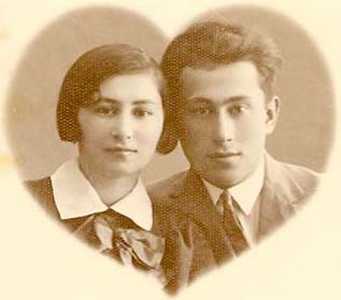

Lisa Finkel.

Ella Finkel.

Ella Finkel.

During the World War II Uri Finkel with his wife, son and youngest daughter was evacuated from Minsk, while his two elder daughters Tsilya and Gila, who came to Rakov to visit their grandfather not long before the German invasion, were burnt together with their granddad – the last rabbi of Rakov (after the Rakov rabbi died, the shochet Hirsch-Shlomo took on his duties). On the same day of 02 February 1942 the wife of Hirsch-Shlomo, Aavigal, was burnt alive in the synagogue with him, together with their daughters: Elka (born in 1906), Lifcha (born in 1910), Ella (1910) and Lisa (1912). They worked at a farmacy in Rakov; and their sons: Ichak (born in 1908) who worked as a teacher and Isaak (1907), who worked as a pharmacist like his sisters. Hirsch-Shlomo Finkel was 72 year old. According to the lists of Yad-Vashem there are 69 persons by the name of Finkel (Pinkel) among the executed Jews of Rakov. Hirsch-Shloma Finkel kept an important historic document – the Pinkas of the Jewish community of Rakov that contained the notes taken from 1810 till 1913. It was written in Yiddish and covered all the main events in the life of the community and every Jewish family. Shortly before the war, Hirsch-Shlomo gave the Pinkas for keeping to his son Uri. Maybe he had some presentiments or just thought that the document should be kept at a safer place than at an old man's. When in the beginning of the war Uri had to leave Minsk he took the Pinkas with him as the most precious thing. After the war Uri Finkel, who mostly lived in Rakov, added the final chapter in Yiddish to the Pinkas, telling about the events of the recent decades. For meny years he kept this unique historic document in a hiding-place. After Uri Finkel's death the Pinkas of Rakov was transferred to the Archives of Israel. It would be great to publish and read this document. I wonder if it's possible... The monument to Ida Rosenthal is planned to be built in Rakov Ida Rosenthal.

Ida Rosenthal.

One more Jewish name returns to Belarus – this time it belongs to a woman who was engaged in making underware. This is Ida Rosenthal. A new attraction for tourists and local citizens may soon appear in Rakov. Severny Lane will be decorated with a sculptural composition dedicated to the inventer of bra. The initiative belongs to the creative workshop “Isloch“. The artists are ready to start working as soon as the necessary amount of money is raised. “The name of Ida Rosenthal is known all over the world in certain circles, that is why we should not forget her here in Belarus, where she comes from.“ - thinks Ales Bely. Ida Kaganovich was born on January 9, 1886 in a Jewish family in Rakov. Ida was the eldest of seven kids. At the age of 16 she went to Warsaw where she worked as a seamstress. After immigrating to the USA Ida found the job at a seemstress shop where, having listened to her clients' complaints about the uncomfortable lingerie, she decided to invent comfortable women's underware. By that time bras had been patented in many countries: in France in 1889 , in Germany in 1891, and in the USA in 1914. But they looked nothing like the present-day bras. It is Ida Rosenthal's ideas that made bras more comfortable: she patented different cup sizes and the breast band construction that allowed to adjust their length. - At those times it was not appropriate to discuss bras in public, - tells Ales Bely. - Maybe this is why only few people know about the author of this invention. In many sources the bra's inventor is simply called “an immigrant from Russia“. At the moment nothing in Rakov reminds of the famous compatriot. Most of her relatives died during the war. Those who survived left for other countries. - We have a monument dedicated to the victims of the Holocaust, - shares his opinion Ales Bely. - And I would like to have more cheerful monuments here as well. It's typical for all Belorussia: the Jewish culture is mostly reflected in the monuments in connection with tragic events. Of course we should never forget about them. But we also need some positive memorials connected with the Jewish culture. Our monument should remind of it. Two years ago the descendants of Ida Rosenthal visited Rakov. Many of them now live in the USA and Israel. The prototype of the monument is already designed – a sculpture in the form of a lantern with crystal elements will light the street. But the scale of the monument will depend on the amount of money we'll manage to raise. - If we could raise as much as 30-35 thousand dollars we would make a real piece of art, - says Vasily Rubtsov, the founder of the creative workshop “Isloch“ in Rakov. - We would be able not only to build the monument but also to make the surrounding area more comfortable: pave the pathways, put the benches to make this place more convenient for both tourists and local residents. We are planning to raise the money till the middle of 2014. We hope to engage as many indifferent people and organizations as possible. And in summer we will decide what to do, depending on the amount raised. The main part of the composition will be made of bronze and black iron. The lantern will be decorated with two cups reminding of Ida Rosenthal's invention. If the image itself is not enough to understand its meaning, a plaque with the invention author's name will be placed there. - We are not afraid to use the crystal elements, - says Vasily. - I don't think anyone would dare to vandalize it. Besides, it's close to our workshop and this place is always crowded. Alexandra Parakhnya1 E. Ioffe, "Pages from the History of the Jews of Belarus", Minsk, 1996, p. 58

|

|||

|

|

Jewish settlements in Minsk regionMinsk • Berezino • Bobr • Borisov • Dolginovo • Dukora • Dzerzhinsk • Ivenets • Myadel • Nesvizh • Obchuga • Pogost • Rakov • Seliba • Slutsk • Svir • Uhvaly • Vileika • |

Main |

New publications |

Contacts |

Site map |

Vitebsk region |

Mogilev region |

Minsk region |