Project «Voices of Jewish settlements. Vitebsk region.»פיתוח קשרי התרבות בין העמים של ישראל ובלרוס

|

|---|

Website search |

|

MainNew publicationsContactsSite mapVitebsk regionMogilev regionMinsk region |

Memories of Raisa Ryzhik Raisa Ryzhik. Moscow, 1996.

Raisa Ryzhik. Moscow, 1996.

My mother’s ancestors originated from Riga and lived there until 1914. Many Jews left the city at the beginning of the First World War after numerous pogroms. My mother’s two sisters moved to Johannesburg and my grandmother, Bela Berman, with her two daughters Basia and Hana ended up in a settlement called Ostrovno, in Vitebsk region. In fact, many Jewish refugees arrived here at that time from the Baltic states. My mother’s name was Basia Berman. She was born in 1898. Hana Berman, her sister, was six years younger than her. In 1916 my mother married Nohim Ryzhik, a Jewish man from Ostrovno. They were happy together and had six children, with me being the fourth. I was an active girl and loved doing the housework: cleaning, washing. I enjoyed everything except studying – I never wanted to do my homework. Our house was full of people – we always had at least ten people at the family table. The family had strict rules of behavior. First grandfather said a prayer and only then we were allowed to eat. Our house was always quiet and calm. My mother was friendly with her parents-in-law.  Raisa Ryzhik. 1945.

Raisa Ryzhik. 1945.

My little sister Bela (the sixth child) died in 1936. My elder brother Abram died of typhus in 1938. He passed away on the day he turned twenty. It was a shock for all of us, especially for mother. After that she somehow became old. When I was walking with her people would say she was my grandmother. So, parents were left with only four of us: Anatoly (born in 1923), Sara (born in 1925), I (born in 1927), and Moisey (born in 1930). My second grandfather (father’s dad), Motl Ruvimovich Ryzhik, was a handyman: a roofer, a cooper, a glasscutter, and a carpenter. On the days when the weather was bad he stayed at home and made baskets and bast shoes. He was not always paid money for his job – sometimes he would get potatoes, mushrooms, honey and so on. He was satisfied with any kind of payment. Life was hard back then – everyone worked on collective farms and was paid with potatoes, cucumbers, barley and linseed oil. Mother worked at a flax mill. Her salary was small but she always received money and sometimes we treated ourselves with herring or sugar. We also grew some vegetables in our small garden. My grandfather was a very religious man. Sometimes I accompanied him to the synagogue. I remember that on Rosh Hashanah we heard the sounds of the shofar, on Yom Kippur everyone was dressed in white clothes and during the Passover grandfather read us the Haggadah. At the beginning of the 30s the Ostrovno synagogue was closed but the religious people still got together at someone’s house to pray. They tried to do it quietly and not attract anyone else’s attention. In the pre-war years the minyan assembled in our house and the scroll of the Torah was stored here as well. We often heard conversations about the war. Every time I heard them I was terrified. At night I covered my head with the blanket to hide from all the mishaps, especially the war. Very often parties were held in Ostrovno, where young people could go to dance. I loved dancing and singing and no one ever prevented me from going there. I was very similar to my father character-wise – he was a very active cheerful man. It was June 22nd, 1941, a Sunday. I can still clearly remember – I was walking in Ostrovno and went to the post office, which had the only radio in our village. People often went there to listen to the latest news, so did I. That day I got acquainted with a new girl, Shura Bogdanova, at the post office. She told me what she had heard on the radio: the war had been officially declared and many towns had been bombed at night. I ran home to share to horrifying news with my family. After hearing my story mother thumped me on the head and exclaimed: “Do you even understand what you are talking about?” Of course, back then I could not understand everything but I sure was very scared. Perhaps everyone was felt scared. Our relatives and acquaintances got together and discussed the trivial question: “What do we do now?” At that time my father’s sister Rahil from Vitebsk came to visit us for the summer holidays. She was twenty. Then uncle Isaak’s wife Liza with two children arrived as well. Isaak, my father’s brother, was mobilized and later died in a battle for Stalingrad. His name, Mendl-Iche Morduhovich Ryzhik, was chiseled on the memorial complex at the Mamayev burial mound. Another father’s sister, aunt Riva, also lived in Ostrovno with her two daughters Dora and Raya. On the third day of the war we decided to leave the town. We only took small bundles and started walking. It was scary because the German planes were bombing the roads. When we were ready to walk out of Ostrovno, a truck drove into our yard. Uncle Abram jumped out of it and told us to get in. In the truck we saw a young man, who had been arrested as a saboteur. We headed for Vitebsk. As soon as we reached the first city buildings uncle Abram told us to get off and promised to come back and help us after dropping off the arrested man. We never saw uncle Abram again and I have no idea what happened to him. Perhaps he shared the fate of thousands soldiers who died on the first days of the war. We had to keep walking. We were close to Smolensk when we found out that the German troops were already close to the city. We could not even hope for evacuation, so grandfather decided we should come back. His words were a law, so we turned back. On the way home we saw fascists convoying prisoners. I will never forget how they were shooting those who fell behind or dropped and could not get up. We were crying all the way. We could not even predict what was going to happen to us. Our poor mother! She calmed us down, saying that the Germans were a civilized and cultured nation, that they would not treat Jews badly. When we returned to Ostrovno we saw that the town had already been occupied by the Germans. On July 19th, 1941 the Nazis issued an order, according to which all the Jews had to leave their houses and move to the ghetto – ten houses in one of the streets. We were also ordered to sew a yellow stripe onto our clothes. Our ghetto was not surrounded with barbed wire, but we were prohibited to walk freely. On the very first day, July 19th, 1941, the fascists shot Aron Shtukmeister. He was only twenty-one. The young handsome man died only because he did not understand why he had to stay at someone else’s house when he had one of his own. But his house was in a different street and his family was not allowed to live there. Aron ignored the order and was killed. Death could enter our house every minute. It was hard for me to comprehend what was happening. We were in the ghetto. Eighteen people were living at our house: our big family and the Shames family, consisting of five people. A Nazi soldier fell into a habit of coming to our house. He said he that was Jewish and that his family had managed to conceal it and move to Hamburg. I can still remember he came in and sat down on a chair in the middle of the big room, like on a throne. I also cannot comprehend why everyone was friendly towards him, why they were answering his questions. I felt only unexplainable aversion. When that fascist came to us I was horrified but at the same time felt curiosity. Once I heard my mother asking him to save my elder sister Sara. The fascist promised he would save her and take her to Hamburg. As I heard that I asked: “And what will happen to me?” The fascist gave a word he would help me as well. Two days later a real tragedy broke into our house. I am now 66. Everything I went through in that war was a nightmare. From time to time I still wake up in cold sweat. I cannot forget how my dearest people were tortured before being killed. I have already mentioned I was a very active and inquisitive girl. I could not stay long at the same place. I knew really well how to enter or exit any house in the village without going outside. I knew how to leave Ostrovno unnoticed. It was an early morning on Tuesday, September 30th, 1941. It was in fact the eve of Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, when it is customary to eat apples with honey, fish and many other delicious dishes. We did not even have a bread crumb in the house. All the adults were gone to look for food. Sara, Moisey and I were at home alone. I came up to the window which faced the road. I saw several cars with armed Germans drive up. They were all dressed in black. They quickly blocked the way to the river and were surrounding the Jewish houses. I called my brother and sister and said: “Look, we need to try and leave the house.” I begged them to follow me but they would not. I could not wait for the adults and something inside me pushed me to run. So I dashed into the yard, squeezed myself through the hole in the fence, and reached the last house in the ghetto running through other people’s yards. I entered the house where the Bogdanovs lived – the family of my new friend. I asked them to hide me. Shura’s mother gave me a passport. I opened the passport and read: Bogdanova Alexandra Alexandrovna, born in 1924, Ukrainian. Shura’s mother explained to me that she was too scared to let me stay, otherwise the Germans would shoot them. Then she added I looked similar to Shura in the photo. I thanked them and ran out. As soon as I ran outside I saw two Germans accompanying my grandfather’s brother Saya. He asked the Bukshtynov family to hide him and came to their house with his violin. The neighbors took his violin, thinking he had hidden money in it, and gave him away to the fascists. I stopped in panic! The fascists looked at me. Saya lowered his eyes pretending he did not know me. The fascists passed me by. I ran out of Ostrovno towards the Russian cemetery. Then I heard the noise of a car. I hid in a shrub. The car stopped, the fascists pushed out the men with spades - the men were forced to dig a ditch. I nearly went insane sitting in that shrub, I completely lost track of time. Then I heard them shooting the men. Several fascists stayed near the ditch while the rest got into the car and left. When the truck came back it was filled with women and children I could not discern the people but I understood the women were saying something to the Nazis. Later I found out that the women told them they would never be forgiven for their deeds. There were a few Russian people who actually came to observe that nightmare. As a child I had never heard that the Russians in Ostrovno were hostile towards Jews or vice versa. There were sometimes rows between neighbors but it was normal. The people understood each other because many Belarusians, Poles and Russians could speak Yiddish, knew and respected our traditions and holidays. Perhaps some people did feel hostility… Having gone mad with fear and grief after seeing the execution I fainted. When I gained consciousness it was dark. I lost track of time and days. When I was crawling towards the execution site I suddenly heard drunken voices. Several policemen were standing next to the ditch and telling each other stories. They were laughing and smoking. Sometimes the ground started moving right under their feet and they stepped aside. I understood from their conversation that the ground on the grave was moving because some of the people had been buried alive. The fascists ordered them to guard the grave so that no one could crawl out. It was unbelievable - I refused to understand that all of my dearest people were lying there. I few days later I also found out that right after the execution the fascists had a big celebration, as if nothing had happened. Among the Nazi policemen were Piotr Savelievich Kovalevsky, Mikhail Pavlovich Sorokin, Anatoly Sergeyevich Bukshtynov. There were also people who hankered after Jewish belongings. For example there was a young woman named Frosia who knew that Frida Krolik had some fabric for a new coat. She brought a Nazi to her house and told him: “Take the fabric from the Jew, I need it.” When fascists shot all the Jews they tore out golden teeth from a woman’s body and Frosia got them as a present. That was how they paid her for love. Half-conscious, I got up and walked to Valkovo, a nearby village. We had a lot of friends there and I decided to go to our family friend’s place – he was the head of the collective farm. I told him that our family had been shot. I could not stop crying and I sincerely believed he felt sorry for me. I came to his house on the third day after the execution. He gave me a place to sleep but I was not able to fall asleep. Suddenly I heard a knock on the door – a young woman entered the house. From their conversation I understood that she was an elementary school teacher from Valkovo. The woman narrated Varlam (the head of the collective farm) about the execution in Ostrovno. “Be quiet, - he said, - I have a Jew sleeping here. I do not know what to do with her. Tomorrow I will take her to the police.” As soon as the woman left I got up and headed for the door. When Varlam inquired where I was going I answered I needed to use the toilet. Naturally, I did not come back. I quietly left the village. There were big barns on the village outskirts where straw and hay were stored. I was walking past them and crying when I heard someone calling me: “Riva, don’t be afraid, come here to the barn.” It was a familiar voice. It was Israel Shumov – he was about forty. He was with Motl Shames, a sixteen-year-old, and a young girl Dora. Dora was from the west of Belarus and destiny had brought her family to Ostrovno. I used to be friendly with her younger sister Lilia so I knew their family really well. When the ghetto was being established, Dora’s parents had paid a Russian family to shelter Dora, so she had been staying with them. As soon as she heard about the execution she came to Ostrovno to find out about her family. She was caught by policemen and kept somewhere in a basement. Mikhail Sorokin, a young man from Ostrovno, was her guard. He promised he would let her go if she slept with him. The girl agreed but first she asked him to let her go outside for a little while. Thus she managed to deceive the policeman and escape. Sorokin was trying to shoot her but missed. Fortunately, Dora escaped. Israel Shumov had lost his wife Peisa and daughter Sima in the execution. He narrated that his fourteen-year-old daughter was first raped and then murdered. The Shumovs were bringing up another child, Israel’s nephew – Sima. She was about seven or eight and her name was also Sima. Her mother had died in childbirth. When the Shumovs were being taken to the execution, a Russian woman ran into the house shouting: “It’s my girl!” and took the little girl away. The woman’s name was Repinia. That night I heard so many eerie stories. I found out how my teacher Stefa Markovna Shehter had died. She was married to Ivan Bukshtynov, a vet. They had two girls. Stefa Markovna was living with her mother-in-law. Her husband was mobilized on the first days of the war. When the fascists came to their house to take her away, she took the children with her. She did not leave them to her mother-in-law. “Let my kids die with me, I do not want anyone to taunt them.” Motl Shames lived with his father. The father was killed and Motl was lucky to escape. Israel Shumov and Motl Shames did not live long – they were brutally killed by policemen in Zhuravli. Dora found the partisans and joined them. After spending the night in the barn we made up our minds to separate. I headed for a village where our acquaintances lived - a family we had helped before. They had a daughter who had been sick and my relative had helped her find a place in a hospital. I decided they might agree to help me. It took me a long time to find those people because I did not even remember their last name. Eventually I succeeded. Their house was located on the edge of the village. I knocked on the door and out came a woman. I got so emotional that I did not even say who I was, I just burst into tears. The woman invited me into the house and gave me water. I told her my story. “We shouldn’t cry, we need to think how we can save you,” – she said. She gave me new clothes and told me I should not speak if some strangers came to the house. (I could not pronounce the Russian “r” very well and it could give me away). We went outside to dig out some potatoes and the her neighbor came up to us, asking who I was. The woman told her I was her nephew from Vitebsk. It was a short conversation and the neighbor left. After a while I found out that the village was frequently visited by partisans. I understood I could not stay with that family for a long time – it put their lives at stake. Unfortunately, I do not remember that woman’s name. Hard life and constant fear erase a lot of positive things from our memory. Once, I saw partisans in the village. I walked towards them – it had to be done carefully, so that no one in the village could see which house I was coming from. I approached one of them – a tall man of about thirty, dressed in black. Later I found out it was the commander of the partisan detachment, Anatoly Fedorovich Kalinin. He was accompanied by his assistant Stanislav Konopiuk. I told them my story. There was another short blond man with them. His name was Semion. He did not look Jewish in the least. Suddenly the commander told him: - The girl claims she is Jewish. Talk to her in your language. So Semion started talking to me in Yiddish. It turned out he was a Ukrainian Jew and we spoke different dialects of the same language. I could not understand everything, especially when he spoke too fast. So I told him that, also in Yiddish. He laughed and told the commander: - There is no doubt she is Jewish. We only speak slightly differently. So they took me with them. In the forest I told them everything I had seen in the village, about the house where all the Jewish belongings had been kept. The commander asked me: - Will you recognize the things they took from the Jews? - Of course, - I replied. We went to the village and entered that house. There was a woman, who started crying, saying it was all a lie. I said: - Ok, let’s see in the basement. We went down to the basement and found coats and hats. I recognized many things that belonged to uncle Isaak, Shamov’s father and other people. We took them and gave them to the partisans from our detachment. After we came back I was asked to talk about my family, about my parents, about what skills I had. I was put up in a big ground shelter and gradually got acquainted with all the people in Kalinin’s detachment. I was especially friendly with Lenia from Georgia, Semion – the Jewish man, frontier guard Nikolai Nosov, and officer Ivan Fedorovich Shevchenko. I remember he told me: “Go to Smolensk and stay with my wife until the end of the war”. I opted to stay with the partisans. When I improved my pronunciation, the commander started sending me for reconnoitering. There were policemen in all the villages and my responsibility was to find out their number and location. Soon our partisans found out about the cruel murder of Shumov and Shames. They decided to revenge and I was sent to the village where they had been killed. - Make sure you do not mention the names of Shumov and Shames, - the commander admonished me. – Pretend you are a pauper and beg for food. But listen carefully to all the information that could be of any use for us. When I came back I informed the commander about everything I had seen in Zhuravli. Then our partisans attacked the police department and destroyed it.  Memorial on the site of execution

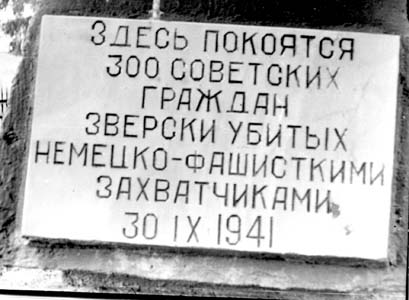

Memorial on the site of executionof ghetto prisoners. Ostrovno. I did not stay long in the detachment. On November 14th, 1941 we heard shooting early in the morning. We had been surrounded with fascists and policemen, and the detachment began to fight back. The commander ordered us to break out of the encirclement. We were taken out by Stanislav Konopiuk and Ivan Shevchenko. I had no shoes on, only stockings – I had had no time to put them on. Then I was wounded on the right leg. Ivan Shevchenko cut off his coat sleeves and made me shoes out of them, which made it much easier to walk. It took us three days to break out of the encirclement. Commander Anatoly Fedorovich Kalinin, frontier guard Nikolai Nosov and many others were lethally wounded in that battle. About fifteen of us broke through. I and Sergey Andriyasov were given a task to get some food. It was November 18th, 1941. So we ended up together, walking from village to village. We pretended to be a brother and sister, orphans. We were begging and moved farther and farther westwards. The frosts were becoming stronger and stronger and it was becoming dangerous to stay in the woods at nights. We reached a peat factory close to Chashniki and were sheltered by Lida Zinchenko. She lived with her two children in one room and let us stay in the kitchen. Sergey treated me really well, he shared everything with me. Sometimes a thought passed my mind that I was afraid of him for some reason. It was unexplainable. Sergey saw it and said: “I used to have two sisters, now I have three. You, Shurochka, are my sister and you should not be afraid.” I recall we sat down and cried. He was my only defender, my brother. …There was a Jewish woman, who lived at the peat factory with her little son. A policeman, Gorolevich, gave her shelter in his flat. And then he decided to shoot her. The rumor that Rosa was going to be shot spread all over the village at once. She was known as an honest and hardworking person. Everyone wanted to say goodbye to her. Even though Gorolevich was from Ostrovno and there were chances he would recognize me, I still went to see her for the last time. I overheard their conversation: Rosa was begging him not to kill her son. She explained that his father was Russian. When she realized he was not going to change his mind she asked him to kill her son first. She needed to be sure he would not suffer. Then he shot her…  Memorial on the site of execution of ghetto prisoners. Ostrovno.

Memorial on the site of execution of ghetto prisoners. Ostrovno.

I do not remember how I got back to the kitchen… We lived there until the beginning of May. One day we went to the market in Chashniki. We were walking there listening to people talking, trying to find partisans. Suddenly we heard a noise; and people began to panic. We were in a roundup – we had no idea that the Germans had a practice of organizing market raids. We were caught and told we would be sent to Germany to work… Then were the years of slave work in Germany, liberation and coming back home. Nobody believed I survived. The remaining relatives, who survived, helped me after the war. One of them told me: “Do not mention you were in Germany. Say you came from evacuation and lost your documents.” A few days later I was handed a new passport and when I opened it I saw that my last name had been changed from Ryzhik to Ryzhikova. I did not tell anyone about my life – I had to make sure no one would find out I had been a prisoner in Germany. For more than forty years I did not have any connections with my relatives, trying not to harm them. People, who had worked in Germany, were considered second-class citizens in our country for a long time. So, I kept silence. On May 26th, 1946 I married Sergey. He was demobilized and we decided to be together. He still called me Shurochka. When our son was born on October 21st, 1948, we called him Alexander – the name that had saved me. When we got married we moved to Grozny. Sergey died of heart failure in 1978. I also had several operations. The pain from losing my family, the people who were so dear to me, never leaves me, not for a minute. Among those, who were executed in Ostrovno are my relatives: My mother Basia Abramovna Berman, father Nohim Motkevich Ryzhik, sister Sara, brother Moisey, grandfather Motke Ruvimovich Ryzhik, grandmother Hienka Ryzhik, grandfather’s brother Saya Ruvimovich Ryzhik, father’s sister Riva Motkevna Ryzhik-Afremova and her two daughters Raya and Dora, father’s sister Rahil Motkevna Ryzhik, Isaak’s wife Liza and their two children Luda and Marik, Lisa’s brother (I do not remember his name; he was 12 or 13), grandmother’s brother Kleiner and his wife Hasia, Hana Galbraih. |

|||

|

|

Jewish settlements in Vitebsk regionVitebsk • Albrehtovo • Babinovichi • Baran • Bayevo • Begoml • Beshenkovichi • Bocheikovo • Bogushevsk • Borkovichi • Braslav • Bychiha • Chashniki • Disna • Dobromysli • Dokshitsy • Druya • Dubrovno • Glubokoye • Gorodok • Kamen • Kohanovo • Kolyshki • Kopys • Krasnopolie • Kublichi • Lepel • Liady • Liozno • Lukoml • Luzhki • Lyntupy • Miory • Obol • Oboltsy • Orsha • Osintorf • Ostrovno • Parafianovo • Plissa • Polotsk • Prozorki • Senno • Sharkovshina • Shumilino • Sirotino • Slaveni• Smolyany • Surazh • Tolochin • Ulla • Verhnedvinsk • Vidzy • Volyntsy • Yanovichi • Yezerishe • Zhary • Ziabki • |

Main |

New publications |

Contacts |

Site map |

Vitebsk region |

Mogilev region |

Minsk region |